Situated in the most eastern part of the Mediterranean Sea and at the intersection of Asia, Africa and Europe, Cyprus has always been a crossroad of civilizations. Through the millennia, Cyprus has demonstrated a continuous dialogue with the Mediterranean, developing close relations with ancient civilizations but always retaining its cultural character and identity.

The archaeological investigation of Cyprus has provided abundant evidence of the ancient inhabitants of the island, their actions, activities, daily life as well as evidence of the political and economic character and role of Cyprus throughout the centuries. Today, the scientific advances enabled the extraction of knowledge and information that was not possible to obtained with the application of conventional methods of the past.

But how did all started?

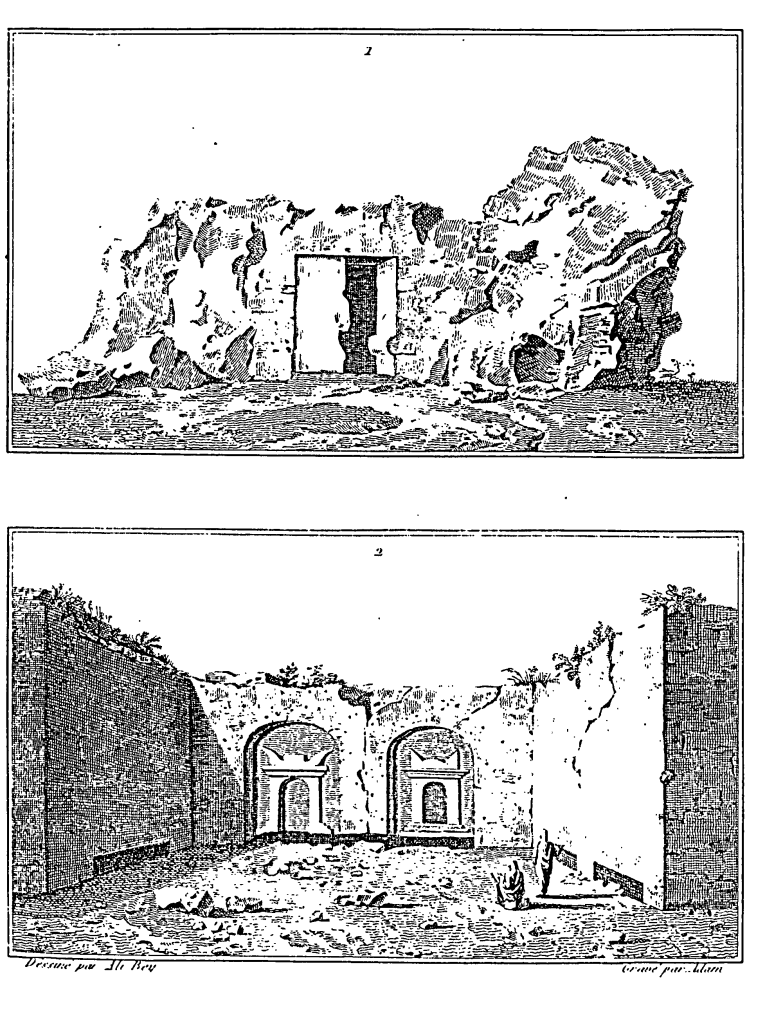

Between the Medieval times and the period of the Ottoman rule in Cyprus, the island was visited by several European travellers as part of their journeys to the Holy Land. In their accounts they describe Cyprus as the birthplace of Aphrodite, the land of Saint Paul and Barnabas and the place where Shakespeare set Othello. In the early 19th century Cyprus is visited by several scholars, antiquarians, artists, diplomas and missionaries. In 1811, Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall, professor at Graz University and diplomat, visited Amathus believing that he had identified the Sanctuary of Aphrodite. In 1816, Otto Von Richter visited Cyprus, recording in his diaries sites, topography and monuments. In 1845, Ludwig Ross, Professor at the University of Halle, publishes a book including a complete section to his visit to Cyprus and his findings at Idalion and Amathus (Severis, 1999). In their accounts, many travellers included ancient ruins of monuments and cities such as Salamis and Paphos, providing an important source of information in which future collectors and early researchers were based on. Some of the most known travellers are Ali Bey (Figure 1), Luigi Mayer, Jose Moreno, Willian Martin Leake and Henry Light (Severis, 1999; Karageorghis, 2000).

Cyprus Archaeology has developed into a scientific discipline as a result of a gradual process. The beginning of archaeological investigations can be traced back to the second half of the 19th and early 20th. This early work was conducted by amateur archaeologists, in majority diplomats, bankers and collectors, with no scientific approach. This early work did not followed a scientific approach, proper recording and documentation but it was only published as a report. With the implementation of related laws already within the 19th century, research institutions started advancing more appropriate excavation techniques and recording (Karageorghis, 2000; Pilides, 2012).

During this early days of Cyprus Archaeology the excavated antiquities were in their majority exported and sold to large foreign museums. This is the time when some of the most known museums in the world begun to form (Figure 2). Until 1869, excavations did not required any permission to be undertaken. But in 1869, the Ottoman Government issued a regulation according to which excavations are only allowed upon permission while export of artefacts was forbidden. One of the most known treasure hunters of Cypriot Antiquities is Luigi Palma di Censola, an American Consul to Cyprus in the 19th century. He was particularly active before the enforcement of the Ottomans’ law thus he was free to dig and export artefacts. After the issue of the Law, he had to grant permissions to excavated in Cyprus but was no longer allowed to export material (Pilides, 2012).

A few years later, in 1874, the Law was replaced with a new, more comprehensive statute according to which all discovered material was the property of the state. Excavations were only granted after license acquisition signed by the Minister of Public Instruction. The excavation findings, according to the new law, were distributed as follows: one third were to be given to the finder, one third to the owner of the land and the remaining one third to the government. Permission to export antiquities was also granted after request, by the Minister of Public Instruction. In 1884, new terms have forbade all exports of antiquities but when the island becomes a British colony, in 1878, the law of 1874 continues to be enforced with the argument that the 1884 terms post-dated the British occupation of Cyprus. It is during this period when Max Ohnefalsch-Richter, on behalf of the British Museum, carried out extensive excavations in several archaeological sites (Figure 3) (Karageorghis, 2000; Pilides, 2012).

In 1905, and after a series of illegal actions involving excavations and antiquities (Pilides, 2012), a new law is passed, the Antiquities Law, by the Legislative Council. The Law stipulated the establishment of the Cyprus Museum and manage to set control to the situation of the 19th century. The new Law however had several flaws, particularly in regards to the excavations, exportation of items and the share. These were resolved through several amendments within the following few years. From 1905 onwards, archaeology in Cyprus shifts towards a more scientific orientation with the conduction of scientific excavations. Menelaos Markides, Curator trained at Oxford University, has conducted some of the first scientific excavations in Cyprus. His work was comprised of recording catalogues, detailed descriptions, plans and drawings. His work was succeeded by Porphyrios Dikaios, known for his excavations at Enkomi, Erimi, Khirokitia, Salamis and Sotira (Figure 4).

It is during this period when the Swedish Cyprus Expedition, under the charismatic Einar Gjerstad, conducted the first comprehensive study of the island’s ancient history. The Swedish Cyprus Expedition (1927-1931) investigated 18 sites dating from the Aceramic Neolithic to Roman times. Some of their most known investigations are those of Petra tou Limniti, ancient Soloi, the sanctuary at Ayia Irini, the palace of Vouni (Figure 5), (Nys, 2012).

Figure 5: The Swedish Cyprus expedition 1927–1931, by John Lindros, Swedish architect and photographer who participated in the Swedish Cyprus Expedition.

In 1935, the Antiquities law has been enacted, establishing the Department of Antiquities of Cyprus. The Department becomes responsible for all scientific investigations at the island, surveys, trial tests. Since then, archaeological research has significantly developed towards a more scientific orientations, beyond items acquisition. Proper scientific methodologies are now applied in surveys and excavations, including comprehensive documentation and recording. Excavated material is from now on researched following standard scientific methods and techniques following current international trends. The rich historical and archaeological contexts of the island attacked the attention of a several foreign Institutions establishing long-term collaborations with the Department of Antiquities.

Research and Text: Cyprus Archaeology Gazette

Bibliography & Sources:

– Karageorghis V. 1979, Studies presented in memory of Porphyrios Dikaios Nicosia.

– Karageorghis, V. 2000. Ancient Art from Cyprus: the Censola Collection. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

– Pilides, 2012. From treasure hunting to systematic excavation. In D. Pilides and N. Papadimitriou, (eds.), Ancient Cyprus: cultures in Dialogue. Department of Antiquities, Cyprus.

– Nys, K. 2012. The Swedish Cyprus Expedition: the first comprehensive study of the island’s ancient history. In D. Pilides and N. Papadimitriou, (eds.), Ancient Cyprus: cultures in Dialogue. Department of Antiquities, Cyprus

Severis, R.C. 1999. Although to Sight Lost, to Memory Dear: Representations of Cyprus by foreign travellers/artists 1700-1955, PhD Thesis, University of Bristol.

-Winbladh, M.L., (1997), An archaeological adventure in Cyprus. The Swedish Cyprus Expedition 1927-1931, Medelhavsmueet.